What’s it like to be a Muslim mystic?

A novel of historical fiction takes us inside the head, and heart, of one Sufi woman

Listen to this essay read aloud.

Several years ago, I thought to myself, “I wish there was a historical fiction book about medieval Muslims in the Middle East.” It would be set in the heart of the Arabic-speaking world, written in English, and give your average American reader a window to the ordinary lives and religiosity of Muslims who lived back then. We were in the middle of rising anti-Muslim hate crimes and newly instituted government policies targeting Muslims. The dehumanization in the public sphere had become commonplace, and in the minds of many Americans, the Middle East and Islam were either defined by stereotypes or shrouded in mystery. Yet at the same time, many others were resisting the scapegoating and eager to get to know Muslims beyond the caricatures they saw in the news.

How happy I was, in 2019, to learn of the publication of Laury Silvers’ The Lover. It’s the first book of historical fiction in her series “The Sufi Mysteries Quartet.” Taking place in the early tenth century, the book follows a Muslim woman named Zaytuna and her community who live in medieval Baghdad, at the height of the Abbasid empire. The story begins when a servant boy from the neighborhood, Zayd, is found dead. Speculation and accusations swirl.

I’ve assigned The Lover to college students in my Introduction to Islam courses, and they—like me—have found it compelling and engrossing. Beyond the suspense of the murder mystery that drives the narrative, Silvers creates a vivid and immersive world that allows readers to envision themselves walking with Zaytuna and her companions through the marketplaces, praying alongside them in the mosque, or sharing simple meals in the neighborhood courtyard.

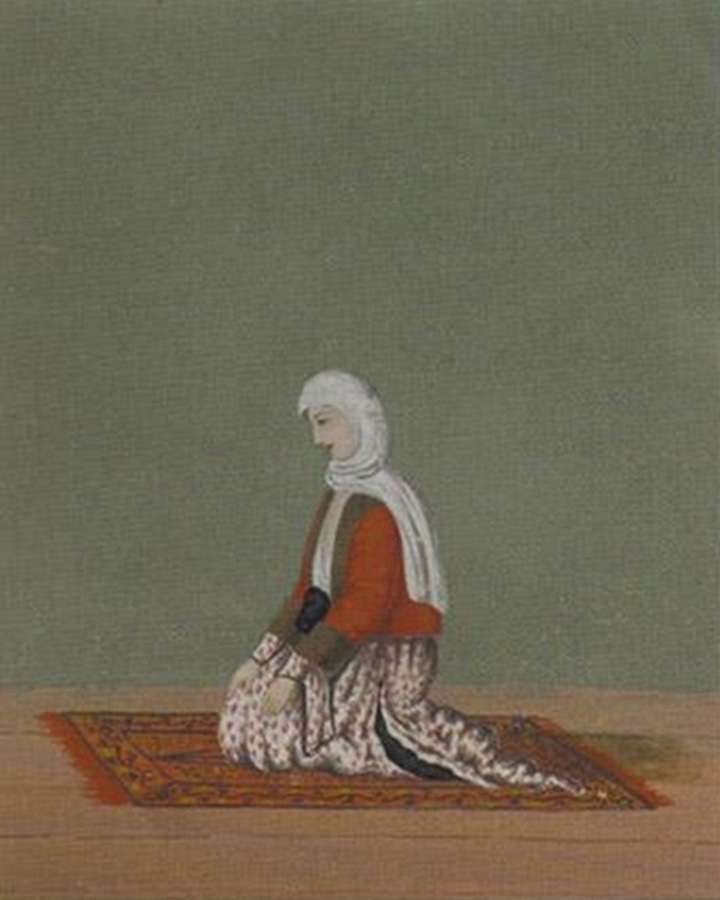

A former academic, Silvers weaves historical insights seamlessly into the prose. Drawing on her expertise as a historian of early Sufism—as well as her own experience as a Sufi—she introduces readers to the world of Islamic mysticism and especially that of female Sufis. Sufism is not a separate sect of Islam but is better understood as a vast tradition that pervades Islam and is taken up by Muslims of all stripes. At the center is the conviction that God can be known and experienced in the here-and-now, that God’s presence can be felt in the course of our daily lives. Like other Muslims, Sufis—the term literally means, ‘one who wears wool’—also focus on the cultivation of good character, seeking the quality of ihsan, or “doing what is beautiful.”

Depending on the time and place, Sufis have had widely varying practices. Some, like Zaytuna, have taken a more ascetical approach, fasting often and eating little, and spending much of the night engaged in ritual prayer. Others, like Zaytuna’s childhood friend Mustafa, are less concerned with ascetical practices but focus more on communal practices like dhikr—chanting words or phrases to achieve “remembrance” of God—or sama’a—listening to music to reach a state of union with God. Sufism is not just a spirituality of the masses, but also of learned people. (Examples are Abu Hamid al-Ghazali, Ibn al-Arabi, and Jalal al-Din Rumi.) In the course of the novel, Silvers introduces readers to some mystic giants of the era, whose names will already be known to students of Islam. Zaytuna’s adopted “uncle” is the great Sufi Abu al-Qasim Junayd, and the rousing preacher Zaytuna’s brother encounters is the famed Mansur al-Hallaj, who was later executed by the authorities for declaring “I am the Truth.”

Each novel in the Sufi Mysteries Quartet gets its title from one of the 99 “beautiful names” of God, and the themes of Silvers’ four books mirror the first four stages of the Sufi path. In the first book, the jaded and cynical Zaytuna is hurting. As an adult, she is still grappling with the early loss of her mother, a renowned, wandering Sufi who—Zaytuna felt—loved God far more than she loved twin children. In The Lover, Zaytuna confronts her past anew and begins to accept God’s love through those around her.

Throughout the prose, Silvers includes Qur’anic passages in the internal monologues and dialogue of the characters. Those who are not familiar with the Qur’an’s turns of phrase may not catch when Silvers is quoting scripture, but readers should know that they are getting a glimpse into how the Qur’an, in a sense, lives inside Muslims, and how its words of challenge and comfort accompany Muslims throughout their lives. Even the main character (whose name means “olive”) and her twin brother, Tein, (whose name means “fig”) are named after a passage in the Qur’an which reads, “By the fig and the olive…We [God] have created humanity in the best of stature.”

Readers are also exposed to the central place of Muhammad in the spiritual lives of the characters. For these Muslims, like so many others, the Prophet is not simply a messenger who lived centuries ago, but someone they have deep love for and think of often. The ever-stubborn Zaytuna shuns the idea of marriage because no man could match the perfect character of the Prophet. She and her friends frequently invoke Muhammad’s humility, voluntary poverty, generosity, mercy, and even his love of cats. We also dive into the contentious world of hadith scholarship—on the sayings of the Prophet Muhammad—through the lens of the Mustafa, Zaytuna’s steady and sweet friend who wants to be something more.

Some of the most intriguing parts of the book are when we are invited inside the protagonists’ heads during their most intense spiritual experiences—like when Zaytuna finds herself flooded by God, or when Ammar, a Shi’a police investigator, sees the dead body of Zayd lying in the dust and is imaginatively transported to Karbala (in modern day Iraq). There, two centuries before, family members of the Prophet Muhammad (including children) were slaughtered by fellow Muslims in a tragic event that Shi’a Muslims commemorate each year on ‘Ashura.

So often in the West, Muslims are portrayed as being solely focused on the political and practical implications of their belief in God. We overlook or deny the possibility that Muslims have authentic personal and communal experiences of God’s presence. This makes Silvers’ presentation of Zaytuna’s mystical experience and Ammar’s imaginative journey all the more powerful. The spiritual lives of these fictional characters help remind us that our Muslim friends and neighbors today also have deep relationships with God, ones that are worth acknowledging and respecting—and even admiring.

The novel digs into many other realities of tenth-century Baghdad: gender dynamics, interfaith relations with Jews and Christians, intrafaith relations between Sunnis and Shi’as, and issues of anti-Black racism (Zaytuna and her brother are of mixed Nubian and Arab heritage). While Silvers is eager to show the nuance and positive aspects of this world, she doesn’t whitewash the history. Zaytuna and her community, who come from the poorer segment of Baghdad society, fully acknowledge that the world they live is marred by injustice: corruption and greed, violence and scapegoating, misogyny and poverty. Yet there is also tremendous empathy, and we see countless people who, despite the difficulty of their life circumstances, care deeply for others and push back against wrongs.

The characters in this book feel like the friends we know from our own lives: complicated, messy people who we can’t help but love anyway. Some of them curse like sailors, and others of them are annoyingly pious. Some of them suppress their emotions in unhealthy ways, and others let their anger and tears flow out on the regular. But all of them are seeking to live lives of integrity and goodness amid the hardships they face.

After reading this novel, it is near impossible to make any generalizations about the groups presented or the world they inhabit. There is incredible diversity among the Muslims—and even among the subgroups—we meet, like the hadith scholars and Sufis. In seeking to be as true to life and history as possible, Silvers naturally pushes back against the harmful stereotyping of Muslims and Islamic history that is so present not just in popular media but also in academia. Silvers didn’t set out to write a novel that would be an antidote to contemporary Islamophobia, but her book certainly helps in that mission.

Perhaps most importantly though, Silver’s The Lover helps each of us reflect back on our own relationships, including our relationship with God. As Zaytuna’s mentor Junayd reminds her:

“God is the Lover through Whom we all love. His love speaks through every moment and every thing even if you cannot hear it or understand it. Trust this. Trust God’s love and begin to let the rest wash away.”

This is a message we all can take to heart.

Readers, join me in ‘digging our well’

Do you have any recommendations for novels set in the Middle East, or that feature Muslim characters? What are your favorite books that weave religion into the narrative?

Share your recs in the comments!

On Laury Silver’s website, you can find resources for teaching about The Lover, as well as informative essays delving into different aspects of the books and her method of researching and writing.

I enjoy reading historical fiction and The Lover's protagonist, Zaytuna, is a character you won't soon forget. And you will learn about a people and a time we are often not familiar with. In this era of Muslim hate and Islamophobia, this series of books will help you see that all people around the world are more like us than we think.